The Value of Horror

Fear. It is one of our most primal, most basic emotions. At one time, it served a vital purpose in our very survival. Yet today, our fears are very different monsters than those which haunted our aboriginal ancestors. The modern era is marked by a more free-floating, less tangible dread; one which cannot simply be outrun or outnumbered. How do we deal with this fear?

Author Steven King has famously said, “We make up horrors to help us cope with the real ones.” Today, I’m going to suggest that we can sometimes best calm our nerves by stimulating them with books like mine – in short, through horror novels.

Throughout history, horror fiction has let people externalize their fears. Beginning with the Gothic era, writers used or created mythological monsters to highlight those things they feared most.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula looks at the fears of female liberation, and of the foreigner arriving on British shores. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a cautionary tale to those who would push the boundaries of science and technology too far. And Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde warns of the de-evolution of morality and society threatened by Darwin’s theory of evolution.

In the 1920s, HP Lovecraft turned the Gothic on its head. He presented a fiction in which the universe itself was inherently opposed to sanity and life – brought on partly by the madness that was World War I. In the fifties, the fear of international Communism brought us The Invasion of the Body Snatchers and countless other books and films depicting an alien invasion of America – a disruption of the postwar middle-class. And in the eighties, any number of slasher villains targeted the sexual transgressions of a generation that seemed to be growing up and apart far too quickly for adult tastes.

Recently, the zombie has returned to the forefront of American horror culture; and it’s a clear reflection of our increasing polarization. Whether you despise Dittoheads or preach against political correctness, it’s easier than ever to see those who don’t agree with you as an unthinking, unstoppable horde. This is not to mention the post-9/11 fears of radical terrorism and illegal immigration.

And today, many authors – myself included – dive into the very real sense of alienation and isolation created by our supposedly interconnected world. How well do you know those you are closest to? What might they do when they are out of your sight? Can we ever truly know one another? Do we really want to?

This, then, is the history of horror. How can we put its monsters into service?

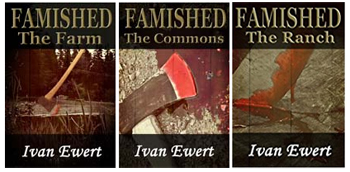

Horror provides us with a remarkable path towards self-actualization. When we can recognize our fears, particularly those which we have buried most deeply, we are able to bring shining truths out of our own inner darkness. In writing the protagonist of Famished, I found myself becoming a stronger, more accomplished individual. I also found greater empathy for those who were raised in a different manner than I, and for those with less education.

Additionally, when we read horror, more than in any other genre, we experience what the Greek tragedians called Catharsis: The process of releasing, and therefore providing relief from, our strong or repressed emotions. In fact, one of the earliest Gothic writers, Anne Radcliffe, stated that she wished her works “to expand the soul and awaken the faculties to a higher degree of life.”

After the monster is slain, after the mists part, we look out into the sunshine. We experience that lifting of tension which has stalked us throughout the pages of our books. We are comforted by the mundane return to the office, by the presence of our significant other, lying safe beside us. The victory of the hero is our victory, and their survival reminds us that we are alive!

Opponents of the horror genre sometimes make the case that watching or reading this matter desensitizes us to violence. In reality, the assertion that violent media results in violent activity has never been borne out by a scientific study. Others claim that their faith instructs them to turn their eyes from this material, though this requires a fairly stretched interpretation of holy texts. And, of course, some people are simply afraid of being afraid.

Yet as Emerson says, “He who is not everyday conquering some fear has not learned the secret of life.”

You know in your heart that this is true – that life and the world call us to face our fears, to acknowledge our secret horrors, and to come away stronger as a result.

Comments are closed.